Specialist in Detail: Cundi Bodhisattva Thangka

The forthcoming Asian Art sale on 20 May 2019 will offer two exceptionally rare and impeccably provenanced Buddhist embroideries. Head of Asian Art, Lazarus Halstead, explores the significance of these important works and their role in averting Tibetan-Nepalese conflict in 1930.

Lot 129. A Chinese embroidered silk ‘Cundi Bodhisattva’ Thangka. Early Qing Dynasty, or earlier. Estimate: £40,000-60,000

Lot 130. A Chinese embroidered silk ‘Lord Yama’ Thangka. Early Qing Dynasty, or earlier. Estimate: £20,000-30,000

Both thangkas come from the collection of His Highness Maharaj Bhim Shumsher Jung Bahadur Rana (1865 – 1932) who was a prominent military leader and who became ruler of Nepal in November 1929 [figure 1].

Figure 2. A depiction of Chiang Kai-shek from the 1940s from the present sale (Lot 239).

Maharaj Bhim Shumsher was well known for his political aptitude when dealing with foreign relations between the Guomindang-ruled China in the north and British India in the south. However, he wasn’t as successful with neighbouring Tibet and the threat of a Tibetan-Nepalese armed conflict came to a head in the spring of 1930.

The conflict, stemmed from the arrest of S. Gyalpo in Lhasa. Gyalpo was viewed by the Nepalese as their own subject, a claim refuted by the Tibetans. His escape from the Nepalese Residency at Lhasa was followed by his arrest by the Tibetan police. This provoked outrage from Maharaj Bhim Shumsher, who in February 1930 ordered the mobilization of the Nepalese forces in preparation for war against Tibet.

The Chinese Head of State Chiang Kai-shek (1887 – 1975) [figure 2] offered military assistance to the Tibetans which was turned down, prompting Chiang Kai-shek to seek a diplomatic solution. He sent the Head of the Mongolian Tibetan Affairs Committee, Ma Fuxiang (1876 – 1932) who arranged for a diplomatic initiative to Nepal. A delegation arrived in September 1930 to meet Maharaj Bhim Shumsher, who was informed that they came in order to “offer the services of the Chinese government to settle the dispute.” (Hsaio-ting Lin, 2006)

Figure 3. A Chinese porcelain panel depicting Maharaj Bhim Shumsher inscribed from Ma Fuxiang, currently in the collection of his descendants.

The delegation presented Maharaj Bhim Shumsher with gifts from Chiang Kai-Shek including the two embroideries. Maharaj Bhim Shumsher also received from Ma Fuxiang, a porcelain plaque depicting himself [figure 3]. Maharaj Bhim Shumsher accepted the gifts but declined all assistance from the Chinese government in resolving the conflict and instead worked with the British-led mediation to arrive at a peaceful settlement. The peaceful outcome allowed Chiang Kai-shek to claim political capital at home for safeguarding the sovereignty and interests of the greater China. Maharaj Bhim Shumsher was made Honorary General of the Chinese Army on 23rd February 1932.

Therefore the two thangkas not only have an impeccable provenance connecting the most significant political figures of China and Nepal of their day, but they also played a crucial and intriguing role in averting war between two sovereign nations.

The Cundi Bodhisattva in Detail

When Cundi Bodhisattva first appeared in China during in the eighth century, she was defined as biezun, an object of specific veneration in her own right and worshipped within her own self-contained cult, only later incorporated within larger constellations of deities.

The Amoghavajra version of the Cundi dharana sutra gave specific instruction as to the iconographic depiction, consolidating and standardising the Cundi’s status, although the deity’s iconography was widely reinterpreted and altered across East Asia over the succeeding centuries. During the Liao Dynasty (907 – 1125) Cundi Bodhisattva gained a prominent foothold as a cult figure in China which was maintained through to the Qing Dynasty.

For the Buddhist practitioner, depictions of Cundi are not simply representational but are also considered to embody her and a spiritual connection which is further enhanced through the recitation of her mantra, the Cundi Dhara?i.

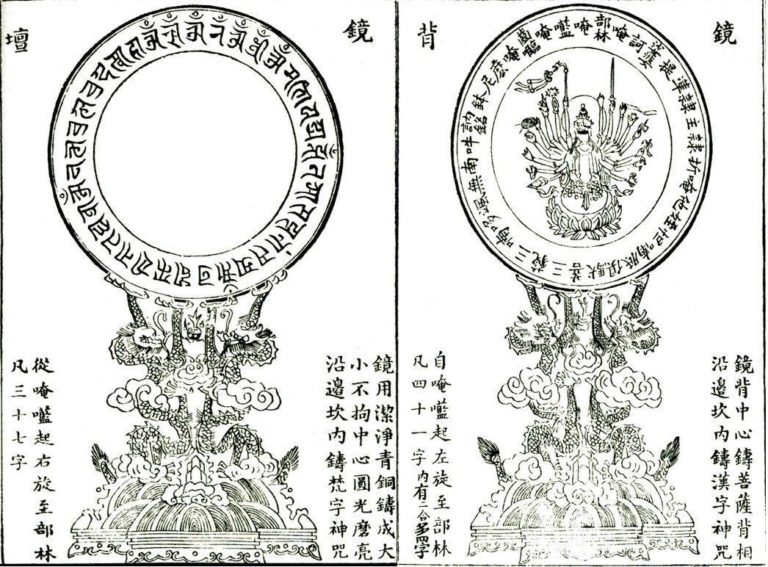

Figure 4. Two pages from the Jing Shisuo, 1821, a compendium of antiques collected by Feng Yunpeng and Feng Yunyuan.

From the Yuan Dynasty onwards, the Cundi was represented on circular bronze mirrors, where her image would be depicted within a border of her mantra written in lança or Chinese script. The deity would often be depicted from the back, so when the practitioner was looking into the smooth side of the mirror and reciting the mantra, it would be as though she was facing him from beyond/within the reflective surface [figure 4].

Figure 5. A painting of Cundi Buddhisattva, Senso-ji Temple,Tokyo, Japan.

Whilst representations of Cundi in bronze, including sculptures, are relatively common, embroidered depictions are exceptionally rare. Paintings therefore are the strongest reference point for the development of two-dimensional depictions of the Bodhisattva. See for example a thirteenth century depiction of Cundi from the Senso-ji Temple in Tokyo, Japan. The Cundi is portrayed here with variant mudra, sitting on a lotus leaf raised above water and with two attendants supporting the leaf [figure 5].

Lot 129. A Chinese embroidered silk ‘Cundi Bodhisattva’ Thangka (detail).

Lot 129 appears to be situated stylistically at some point on a continuum between the two images, although radiocarbon testing of this lot produced a date from the early Qing Dynasty (results available on request). However, the work is framed within a woven-silk border of lotus flowers, with two attendants of attenuated form either side of the Cundi which strongly recalls iconography of the Ming period.

The medium of embroidered silk is perfectly suited to convey the majesty of Cundi. The gold thread, embroidered in the characteristically early split stitch technique is made up of twisted threads over the face which distributes reflected light across the surface in an even tone. In contrast the smooth threads over the arms and shoulders, covers the body in a golden glow.

The three-dimensional treatment of the Cundi’s nose further draws the figure out from the embroidered plane and the green sash over the shoulders is layered above the skin, along with the other layers of clothing, providing depth to the image and dynamic tension to the pose.

This piece has clearly had a religious life spanning the centuries since its creation and whilst the provenance goes back to 1930 its locations before then remain a mystery consistent with the figure’s enigmatic character.

The forthcoming Asian Art sale will take place on Monday 20th May at 11am.

Literature: Hsaio-ting Lin, Tibet and Nationalist China’s Frontier: Intrigues and Ethnopolitics, 1928-49, 2006.