Seven Works by Louis Christian Hess

The Early Years

Hess was born in Bolzano in the South Tyrol; his father was an office clerk; his mother, by contrast, was Austrian bourgeoisie. In 1906 the family moved to Innsbruck where Hess studied at the Staatsgewerbeschule (the State Institute of Art), and in 1915 he had his first exhibition of drawings and prints at the Thurn und Taxishof Galerie.

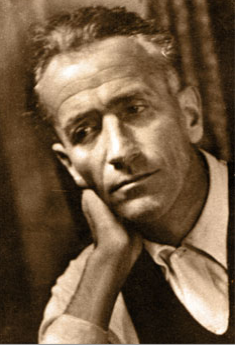

A photograph of the artist Louis Christian Hess

His formative years, however, were overshadowed by a succession of family bereavements and the horrors of the First World War. Between the ages of 10 and 22, he lost his father and two of his three sisters, Rosa Anna and Bertha, to tuberculosis, and learnt of the death of his mother whilst on the German front line, where he fought in the battles of Verdun, the Somme and Aisne. By the end of the war, he had one remaining sibling, his sister Emma, whom he remained close to. But his wartime experiences combined with unfolding family tragedies scarred him psychologically and left him with a nervous disposition for the rest of his life.

Munich, German Expressionism and the Neue Sachlichkeit - 1920s

In 1919, during the early years of the Weimar Republic, Hess began studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich under Carl Johann Becker-Gundahl. Although the Academy was conservative in outlook, it was there that Hess developed his natural skill as a colourist. In 1920 he exhibited in the Ausstellung Junger Munchner – Graphische Kunstwerkastatten, where his work was singled out by the critic George Jacob Wolf for having ‘an uncommonly developed sense of colour’.

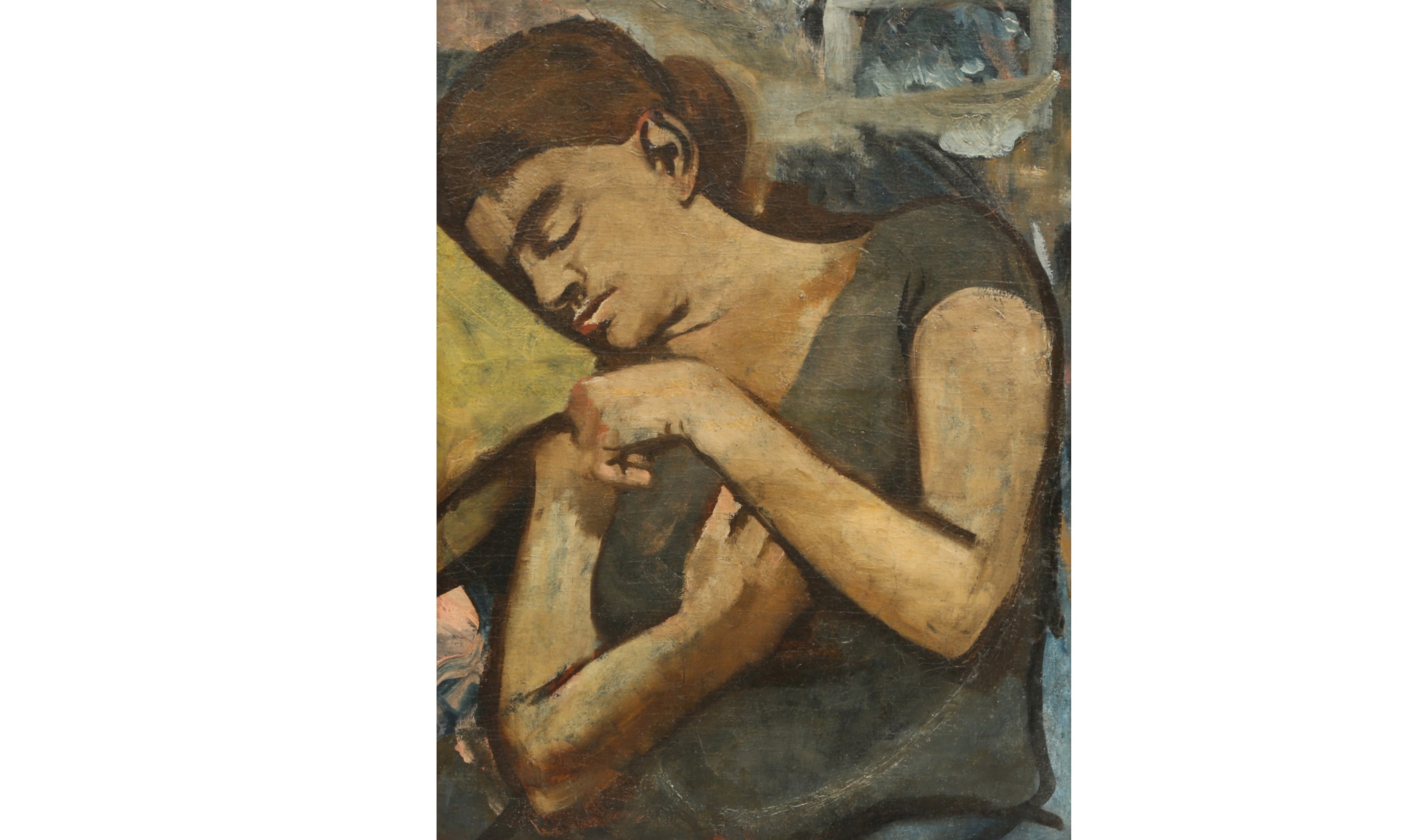

Fig.1 - Louis Christian Hess, Resting Woman (1925), £3,000-5,000

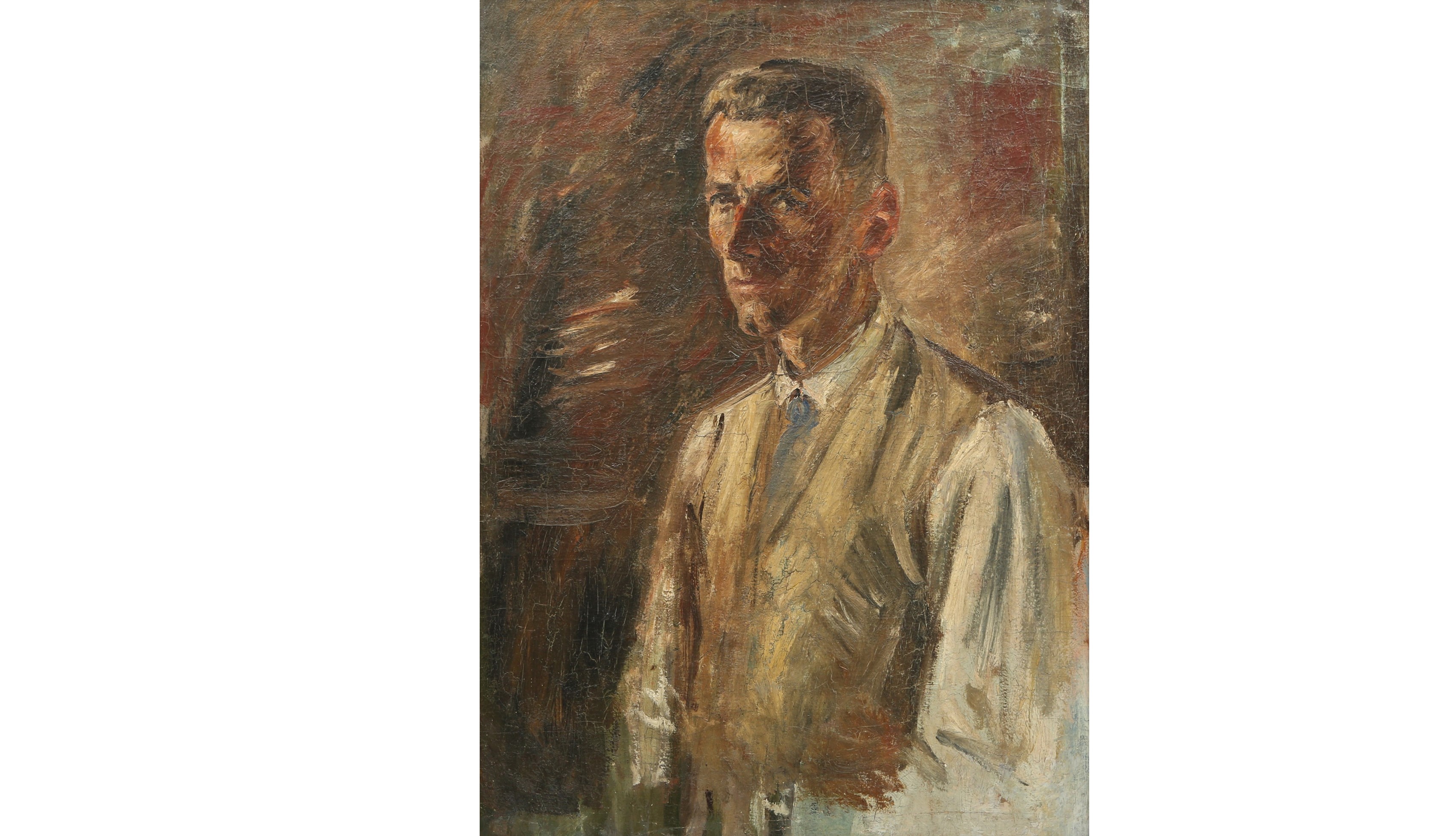

Munich in the 1920s became home to the artists most closely associated with Neue Sachlichkeit (The New Objectivity) – amongst them Otto Dix, George Scholz, Christian Schad and Max Beckmann. Although Hess was not formally associated with the movement, he became friends with Beckmann in the late 1920s, and the influence of these artists can clearly be seen in his oeuvre. Friend I (1930) echoes many tendencies found in Beckmann’s works of the period: the plasticity of the figure, the powerful use of light and dark, the black outlines that brilliantly carve out the form of the sitter and the use of the deliberately vibrant rich, almost garish yellow.

In Friend I and in his 1924 Self-portrait, there are also similarities with Christian Schad’s Neue Sachlichkeit style. Like Schad’s portraits, Hess paints himself with stark simplicity and realism, confronting the viewer face on. In Friend I the figure glances away from the viewer, preoccupied in thought, creating a sense of mystery within the painting, a quality found in many of Schad’s portraits of the period.

Fig. 2 - Louis Christian Hess, Friend 1 (1930), £6,000-8,000

Another artist and friend who influenced Hess was the German Expressionist painter Karl Hofer. In Friend I Hess explores Hofer’s interest in non-representational colours to provoke emotional responses with the vibrant yellow standing out against the dark background. Karl Hofer was also a skilled master of form and Hess has demonstrated this in his adept rendering of the shadowed folds of the sitter’s clothing.

Fig. 3 - Louis Christian Hess, Self-portrait (1924), £5,000-7,000

Hess’s Frauenkirche (1919) linocut reflects his broader interest in the work of the Expressionists, in particular the woodcuts of Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, who worked almost exclusively in this medium after WWI. Striking similarities can be seen with Schmidt-Rottluff’s woodcut Stadtbild aus Soest (1923) in The Cleveland Museum of Art. In both woodcuts, the church spires extend to the sky, whilst the jagged angles and patterns of light give their portrayals of these German cities a vivid energy.

Fig. 4 - Louis Christian Hess, Frauenkirche (1919), £200-300

Sicily - 1920s

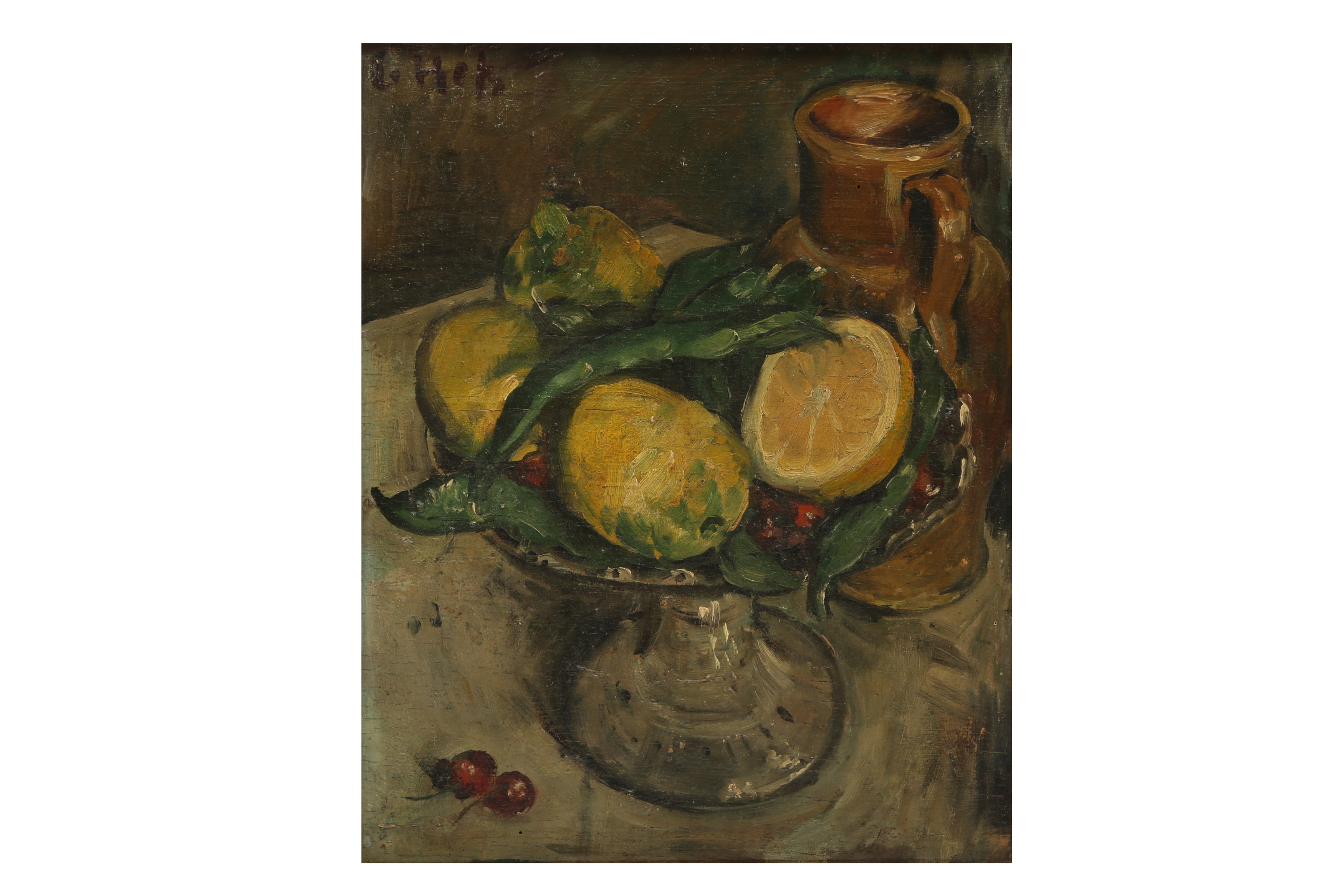

In 1925 Hess travelled to Messina, Sicily to visit his sister Emma. There, he experienced an artistic epiphany, revelling in the possibilities of colour and light that the sun-drenched Mediterranean island offered. Hess wrote to his friends in Germany that he had found paradise, and so inspired was he that in 1926 he produced a series of 60 vibrant Sicilian etchings. Hess repeatedly returned to Sicily during the later 1920s and in 1927 he executed a series of bold colourful works for an exhibition in Germany. He also decorated the Mayer family villa in Wismar, northern Germany, with exuberant Sicilian-inspired frescoes.

Fig. 5 - Louis Christian Hess, Still life with Lemons (1925), £1,500-2,000

The Juryfreie - 1930s

Hess joined the progressive Juryfreie in Munich in 1929, becoming one of the group’s leaders. The Juryfreie (Jury-free) was self-adjudicating and open to artists from all traditions, but most adherents were Modernists. During the 1920s and 1930s, it was the most liberal exhibiting body in Munich, with former members including Wassily Kandinsky and Oskar Schlemmer. The Juryfreie curated many notable exhibitions, including in 1929 Abstract Artists and Surrealists featuring the work of Arp, Ernst, Klee, Miro, Picasso and Mondrian. In the July 1929 issue of Aus meinem Künstnotizbuch, art critic Wilhelm Hausenstein wrote the ‘Juryfreie reveals itself as a prominent artistic group... I notice Christian Hess, Josef Scharl, Fritz Burkhardt, Grassmann, Panizza and sculptors such as Spengler and Zeh’.

Fig. 6 - Louis Christian Hess drinking beer from a bottle with members of the Juryfreie, Munich 1929

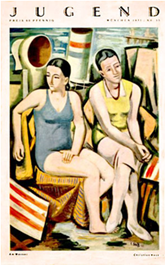

During this period Hess began to receive wider recognition, with many art magazines reproducing his works. In 1931 the Munich magazine Jugend illustrated the central panel of his oil triptych Am Wasser shown at the Secession exhibition at the Glaspalast in Munich. Friend I (1930) was one of two studies for the figure on the right in this accomplished painting. Hess exhibited in further exhibitions with the Secessionists at the Glaspalast in the early 1930s, where several of his works were destroyed in a catastrophic fire in June 1931, including Am Wasser. The event marked a devastating blow for Hess, who sent a postcard to his sister Emma illustrating the ruins of the Glaspalast fire on which he wrote ‘here lie my works: all burnt’.

Fig.7 - Am Wasser (1930) reproduced on the cover of the magazine Jugend in 1931

In 1931, following public demonstrations by the Juryfreie, Hess and others were banned from the group by the far-right paramilitary wing the SA, and in 1934, with Hitler’s rise to power, the Juryfreie was disbanded as they were viewed as ‘culturally bolshevic’.

Years of Exile

Following the financial crash of 1929, the on-set of the Depression and widespread unemployment, Hess wrote to his sister Emma in 1932 ‘Financially, circumstances have never been so catastrophic. Wherever you are and whoever you speak to, everyone grumbles…and politics are the main theme.’

The following year, with mounting political instability, and with his art viewed as degenerate by the authorities, Hess escaped Germany for Sicily. There he joined his sister to live with his wife the actress Cecilia Faesy. His works during this period were inspired by the landscape and island life.

Fig.8 - Louis Christian Hess, Harbour scene (1933), £600-800

But his years with his wife in Sicily were short-lived. In 1936 Cecilia left him to travel to Switzerland. The rupture caused him extreme mental instability and pushed him to attempted suicide. Hess lived for a further two years in Sicily returning to Munich in 1938, leaving many of his paintings in the care of his sister. Forced to conscript in 1940, due to his fragile health Hess was assigned work at the post office, but in December of 1940, he fell seriously ill and was discharged. He returned to Austria and in 1944 died in hospital at the age of 48 after an air raid over Innsbruck.

During the Second World War Messina suffered extensive bombing due to its strategic position. To protect the paintings her brother left behind him, Emma rolled and wrapped them, and stored them in her nearest air-raid shelter. After Hess’s death, Emma oversaw his estate and the survival of a significant number of his work. The seven lots to be offered in our sale on Tuesday 30 March come from the group that Hess delivered to his sister when he returned to Messina in 1936.

These works will feature in our upcoming British & European Fine Art on Tuesday 30 March at 2 pm. For more information contact Ishbel Gray.