Collector's Guide: Incunabula & the Infancy of Printing

Ahead of the Printed Books & Manuscripts auction on 27 September, Specialist Dr. Carmen Donia takes a closer look at incunabula - otherwise known as early printed books printed before 1501, shares expert insight into the notably sought-after pieces at auction and offers top tips on conservation.

'Incunabula' is the plural of the Latin word 'incunabulum', meaning 'swaddling clothes' or cradle, and refers to all books that were printed with metal type from the beginning of Gutenberg movable type printing press around 1455, up to the year 1501. This date marks the end of the 'infancy of printing', as it rapidly spread to many centres across Europe and into America. It was in fact around 1530 that a transformation in the appearance of the book took place. The term 'incunabula' was introduced in a treatise on the art of printing much later, in Cologne (1639), to describe the first printed books of the 15th century.

The Gutemberg’s Bible, printed in Magonza in 1453-55, is the first actual book printed in the West with moveable metal type.

'Gutemberg’s invention revolutionised the distribution of knowledge by producing many accurate copies of a single book. Before that, books in Europe during the Middle Age were copied by hand (manuscripts) and the vast majority were Christian religious works. They were richly decorated with lettering known as illumination which could be applied by hand after the printing process.' - Dr. Carmen Donia

Incunabula were initially printed in the same style as manuscripts and continued the tradition of the scribes, making use of columns, marginal notes and textual contractions and elision to reduce the volume of the book. Many incunabula were designed to be rubricated by hand with flourishing initials and other decorations. Furthermore, following the custom of manuscripts, the first printed books lacked title pages in the modern sense. Very brief information on the contents and the author, appeared on the recto side of the first leaf, while the name of the printer, year and place of publication, as long as the name of the person who commissioned the printing, could be found in the colophon, a section at the end of the text consisting of a few lines. Incunabula could even incorporate fragments from manuscripts, mostly used as flyleaves and pastedowns, but sometimes also as binding covers.

Lot 163

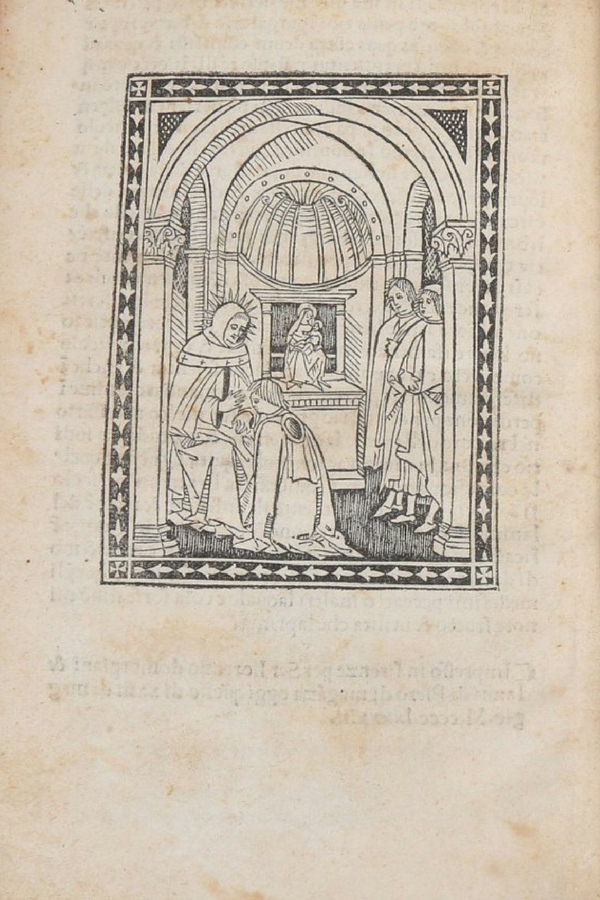

The early printed books often included beautiful illustrations. They were prepared both from relief woodcuts and from intaglio copperplate, hand engraved by skilled artists, before moveable type was invented. During the 15th and for most of the following century, woodcuts were much more common in books than copperplates as they could be printed along with the text.

'Even though early printed books imitated manuscripts, the process of their production was much quicker and cheaper, as the result of a number of changes and innovations in the design of the book, including a reduction in size, standardisation of type face and the addition of title page and pagination. The process of printing involved now numerous figures: printers, publishers and book sellers, as well as artisans.' - Dr. Carmen Donia

In the years following the appearance of Gutemberg’s Bible, printing spread particularly through German speaking regions and Italy.

Lot 22

In Germany, Basel and Nuremberg were among the most important centres for printing. It was here that some of the most remarkable books were produced, such as the edition of Jean Gerson’s theological works in 3 volumes (1489-1494) and the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493).

Jean Gerson (1363-1429) was a French scholar, reformer, and Chancellor of the University of Paris. His collected works were printed ten times in Cologne, Strasbourg, Nuremberg, Basel and Paris. Each volume is embellished by a beautiful frontispiece depicting the author as a Christian Pilgrim. The design of the woodcut has been attributed to the artist and engraver Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528.)

The image recurs several times in other works of the same period, rendered in different ways but with common elements that evoke the mystical journey of the author in the world. The scene represents a mountainous landscape with a castle and the traveller Gerson walking a rugged path, accompanied by a dog. He carries a coat of arms with the symbol of the sun, moon and stars, and a winged heart, and is equipped with the knapsack - all typical attributes of the pilgrim.

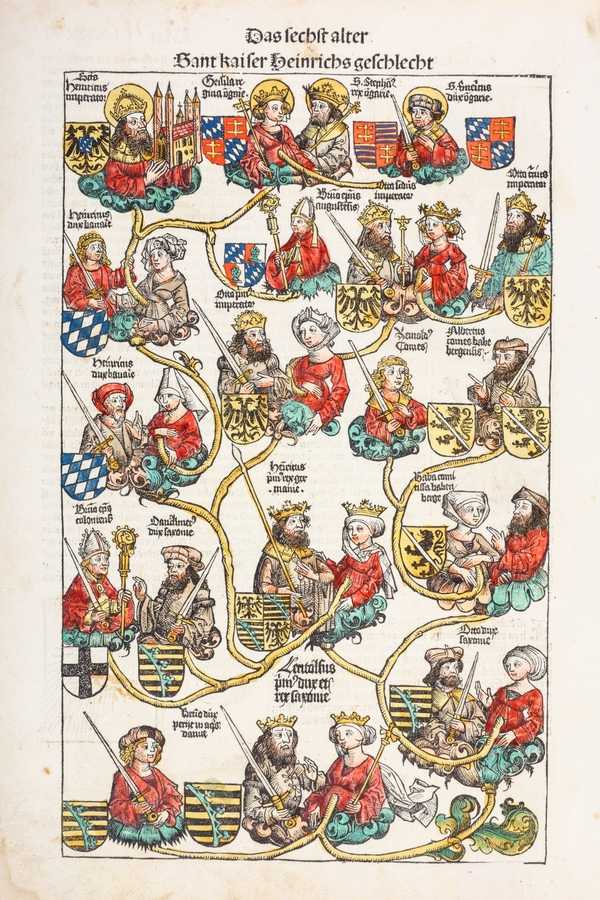

Among the printers active in Nuremberg, the most productive was Anton Koberger, godfather of Dürer. His books were expensive and well made. He published the monumental Nuremberg Chronicle (1493) which demanded complex planning. Dr. Hartmann Schedel (1440-1514), a member of the City’s circle of humanists, compiled the text in Latin and the scribe George Alt was engaged to produce a translation into German for a vernacular edition. Three years were spent producing over 1800 woodcuts after Michael Wolgemut drawings. Most of the illustrations are pictures of cities or people and two maps (one of the world and one of Germany).

'The Chronicle is a most attractive object for collectors and booksellers, as it holds an important place in the tradition of illustrated books.' - Dr. Carmen Donia

Lot 206

Nowadays copies of both the Latin and German editions of the Chronicle survive in Institutions and private collections, as well as fragments and individual leaves.

The collecting of early printed works or even individual leaves has been widely accepted from the bibliophile’s world and collectors can follow specific conservation tips. For instance, the enemies of all old documents are heat, humidity and sunlight.

'They should have limited contact with strong light and be stored in a dry place, ideally never a basement or attic where change of temperature and humidity can cause deterioration.' - Dr. Carmen Donia