Chinese Export Silver is a fascinating and often underappreciated area of fine silver collecting. Created by highly skilled Chinese silversmiths, often working to Western tastes and forms, these pieces combine expert craftsmanship with rich cultural detail.

At Chiswick Auctions, we are proud to have handled many important examples of Chinese Export Silver, reflecting a diverse range of regions, makers and techniques. This guide provides an introduction to the world of Chinese Export Silver, its makers, and how to identify pieces of value and significance.

An early 19th century Chinese Export silver teapot stand, Canton circa 1820 mark of Tu Hopp, sold for £938 incl. premium

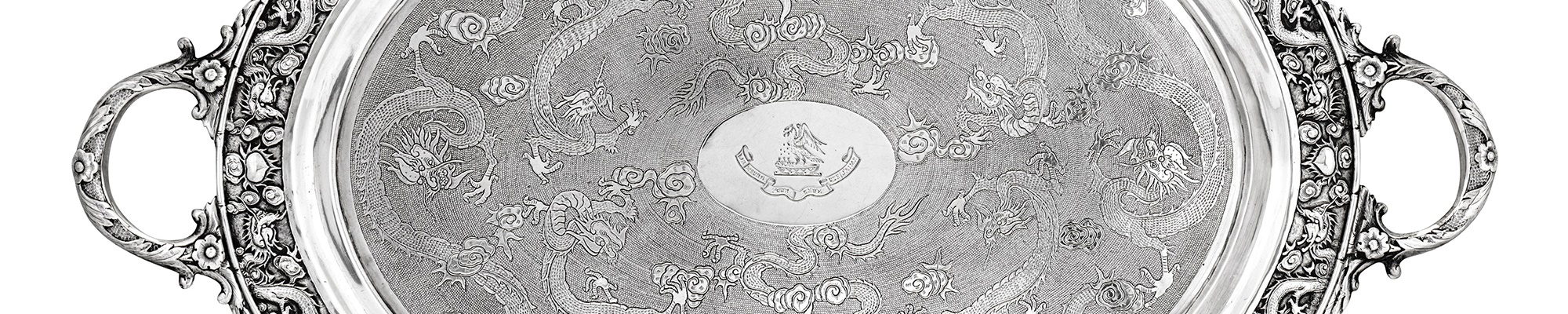

From the late 18th century onwards, Chinese artisans began producing silver for export, particularly to Britain, Europe and America. These works mimicked Western forms such as salts, mugs, flatware, tea services and cruet sets. While stylistically Western, they were often decorated with distinctly Chinese motifs.

In place of formal hallmarks like those found on British silver, these early pieces often bore so-called “pseudo marks” which resembled British assay marks but had no official status. These marks often referred to the retailer rather than the actual maker.

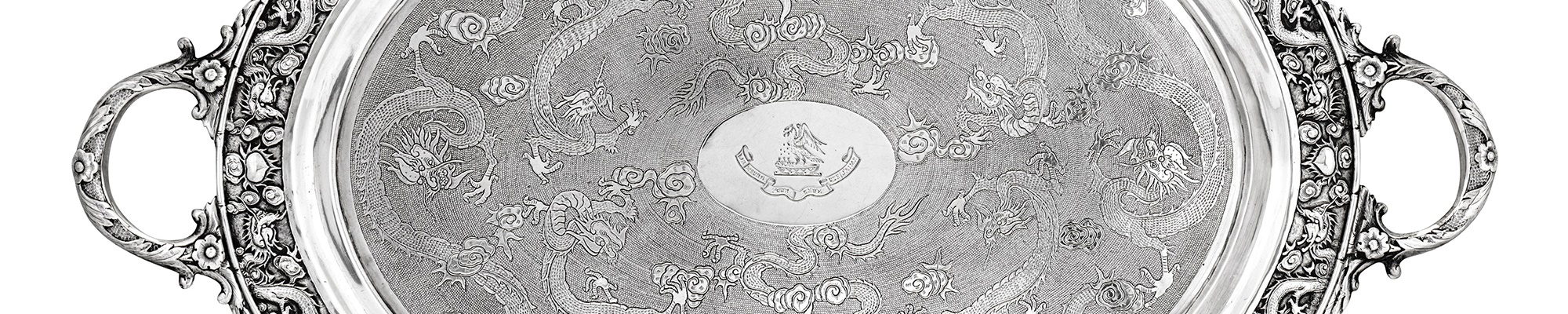

By the mid-19th century, styles began to shift. Pieces became more overtly Chinese in aesthetic, with dragons, phoenixes and bamboo featuring prominently. At the same time, more accurate maker’s marks in Chinese characters began to appear.

Chinese Export Silver was produced in several key locations, each developing its own style:

Canton: The main centre for silver production, with strong export links via Hong Kong and Macau. Cantonese silver often includes fine pierced and chased decoration.

Shanghai: Known for refined and elegant forms, often retailed by firms such as Luen Hing and Luen Wo.

Tianjin, Jiujiang, Hong Kong and Beijing: These cities also produced silver for export, sometimes reflecting regional preferences or international influence.

A mid to late 19th century Chinese export silver double gourd tea caddy or wine bottle, Canton circa 1870 retailed by Cum Shing, sold for £2,125 incl. prem

An early 20th century Chinese export silver three-piece tea service, Shanghai circa 1910

retailed by Luen Hing, sold for £2,375 incl. prem

An early 20th century Chinese Export silver tray, Tianjin circa 1920 retailed by Ye Ching Company, sold for £1,000 incl. prem

A mid-20th century Chinese export silver four-piece tea and coffee service, Hong Kong circa 1940 retailed by Tack Hing, sold for £2,250 incl. prem

A pair of early 20th century Chinese Export silver vases, Jiujiang circa 1900 by Tu Qing He, sold for £1,000 incl. prem

An early 20th century Chinese Export silver sauce boat, Beijing circa 1930 by Sheng Yuan, sold for £188 incl. prem

Retailers’ marks are typically found in Latin characters. They identify the business that sold the silver, not the workshop or artisan that made it. One of the most common examples is WH for Wang Hing, a large and successful silver retailer based in Canton and later Hong Kong.

These marks can also include Arabic numerals such as “90” or “85”, which are believed to refer to silver content. However, without a formal assay system in China at the time, these numbers should not be relied on to determine purity.

It is important to note that retailers’ marks do not represent the silversmith or confirm the quality of the work. The retailer often acted as a distributor, sourcing items from multiple workshops.

More accurate attribution lies with artisan’s marks, usually in Chinese characters. These marks identify the workshop or silversmith responsible for the actual production. They are the closest equivalent to British or European maker’s marks.

While many of these marks remain anonymous, some are well known for producing work of the highest quality. Two notable examples include:

Sui Chang (遂昌): Known for superbly chased and pierced silver, including large trays and figural pieces.

Qiu Ji (求記): Associated with finely engraved scenes, often of Chinese village life or nature.

Artisan’s marks can be found alongside various retailer’s marks, indicating widespread distribution of their work.

A late 19th / early 20th century Chinese Export silver bowl, Canton circa 1900 retailed by Luen Wo

Marked underneath SHANGHAI, LUEN.WO and with artisan mark QIU JI 求記 (a Canton workshop)

sold for £1,188 incl. prem

A late 19th / early 20th century Chinese Export silver biscuit box, Shanghai circa 1900 retailed by Luen Wo

Marked underneath with retailer’s mark LW twice and artisan mark HU ZHEN 華珍 (a Shanghai workshop)

sold for £1,750 incl. prem

Chinese Export Silver is distinguished by its decorative richness and expert execution. Common techniques include:

Embossing: Combining repoussé (pushed from the reverse) and chasing (worked from the front) to create deep relief.

Cast and Applied: Decoration is formed separately, then applied to the surface, often seen in dragon or floral motifs.

Piercing: Designs are created by cutting away parts of the metal, often used to create openwork borders or panels.

Flat Chasing: Patterns are hammered into the surface to resemble engraving, without removing any silver.

Matting: The surface is gently textured to create a soft, diffused finish.

Wire and Sheet Work: Small components such as dragon horns or flower petals are formed from fine wire or cut sheet and applied.

These techniques, often used in combination, contribute to the intricate and three-dimensional quality of Chinese Export Silver.

Because there was no formal hallmarking system in China, accurate identification relies on close examination of both the retailer’s and artisan’s marks. Proper attribution helps collectors understand where, when and by whom a piece was made, and provides the basis for accurate valuation.

Chinese Export Silver is increasingly recognised as an important category within antique silver. Demand continues to grow among collectors and institutions alike, particularly for pieces with clear marks, provenance, and fine workmanship.

Chinese Export Silver reflects a remarkable fusion of East and West, blending European forms with Chinese craftsmanship and decorative motifs. With its richness of detail, variety of forms and historical interest, it represents a rewarding area for collectors and connoisseurs alike.

Contact John Rogers, Head of Silver & Objects of Vertu at Chiswick Auctions, via john.rogers@chiswickauctions.co.uk, or submit an online valuation today.

Dr Adrien Von Ferscht is the leading scholar in the study of Chinese export silver and its marks, publishing this research in the online third edition of Chinese Export Silver – the definitive collector’s guide (2015). We are grateful to Dr Adrien for the generous support given to the department over the years with aid to cataloguing and identifying marks for Chinese Export silver.

For further examples of Chinese Export silver, but with outdated mark attributions, see:

Forbes, Crosby, H.A., Devereux Kernan, J., & Wilkins, R.S. (1975) Chinese Export Silver 1785 to 1885. Massachusetts: Museum of the American China Trade.

Also:

Devereux Kernan, J. (1985) The Chait Collection of Chinese Export Silver. New York: Chait Gallery