Birds and Blossoms: The Enduring Allure of Kacho-e in Japanese Art

The theme of birds and flowers, known in Japanese as kacho-e, holds a revered place in traditional painting. As one of the three major genres of East Asian art (alongside landscape and figure painting), kacho-e originated in Chinese academic painting before being reimagined in Japan. The result was a uniquely Japanese expression, characterised by delicacy, harmony, and a deep appreciation for seasonal beauty.

Ink and Influence: The Medieval Origins

The earliest examples of kacho-e emerged in 14th-century Japan, a period shaped by Zen Buddhism and the influence of Chinese culture. Buddhist monks produced simple, meditative ink drawings of plum blossoms, lotus flowers, and birds. These compositions, rich in symbolic and spiritual meaning, were inspired by imported paintings from the Chinese Song and Yuan dynasties.

Over time, Japanese artists adapted the genre to local tastes. They favoured asymmetry, empty space, and restrained detail, placing serenity and suggestion at the heart of the image

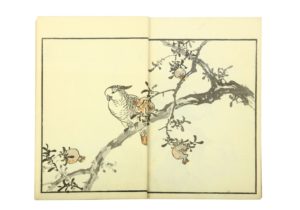

KONO BAIREI (1844 – 1895).

The Edo Period: Power, Symbolism, and Splendour

Under the Tokugawa Shogunate (1603–1868), Japan entered a long era of peace and prosperity. With the end of civil conflict came a blossoming of the decorative arts. Kacho-e flourished in elite homes, where gold-leaf screens, wall panels, and hanging scrolls often featured birds in flight or perched among flowering branches.

Symbolism was key. Cranes, sparrows, cherry blossoms, and chrysanthemums conveyed seasonal cycles, good fortune, and the fleeting nature of life. For the ruling classes, such imagery was not only beautiful but also a visual language of prosperity and social status.

A Japanese embroidered hanging.

The Tokugawa Renaissance: Isolation and Innovation

During the Edo period’s isolationist policy, Japan saw limited foreign influence. Yet cultural life flourished, particularly in woodblock printing. Innovations in full-colour techniques allowed artists such as Hokusai and Hiroshige to explore kacho-e in striking vertical formats known as tanzaku.

These prints brought birds and flowers into everyday homes. Whether showing sparrows among cherry blossoms or nightingales resting in chrysanthemums, the prints conveyed elegance, calm, and seasonal awareness.

ANDO HIROSHIGE (1797 – 1858).

The Meiji Era: New Audiences, Lasting Appeal

The Meiji Restoration (1868–1912) brought profound transformation as Japan opened to the West. Artists once employed by feudal lords turned to new markets, producing decorative pieces for international collectors. Kacho-e evolved into more naturalistic and finely detailed works, while still honouring their symbolic roots.

As Japonisme took hold in Europe and America, kacho-e found favour among Western collectors. Today, both antique and Meiji-period examples remain popular, admired for their craftsmanship, quiet elegance, and cultural significance.

Interested in the value of your Japanese art?

Whether you own woodblock prints, decorative hangings or Meiji-era craftsmanship, your pieces may hold significant historical and market value.

Get in touch with our Asian Art Department for a complimentary valuation:

Email: asian@chiswickauctions.co.uk

or submit an Online Valuation

Our specialists are happy to advise on individual works or entire collections.