The silverware produced during the Raj period represents a remarkable chapter in the history of Indian decorative arts. Following the formal establishment of British India in 1858, a distinctive category of silver emerged that blended Western forms with Indian decorative traditions. This hybridised style developed through both adaptation of traditional Indian motifs and the influence of international exhibitions that encouraged innovation. Anglo-Indian silver is notable for its regional diversity and the cross-pollination of styles across the subcontinent.

At Chiswick Auctions, we have been privileged to handle many fine examples of Anglo-Indian silver, and this guide aims to offer collectors and enthusiasts a detailed overview of the key regional styles.

Southern India produced some of the most recognisable forms of Raj silver, particularly in the city of Madras. Here, firms such as Peter Orr and Sons popularised ‘Swami pattern’ silver, characterised by depictions of Hindu deities, often identified by the animal (vahana) they ride. This highly decorative style gained royal approval after being presented to the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) during his visit to India in 1875–76.

Variations of Swami silver developed in Trichinopoly and Bangalore, each with subtle distinctions in background decoration and composition. The Swami aesthetic eventually spread further afield to Bombay, Poona and Lucknow, often resulting in stylistic hybrids.

A late 19th / early 20th century Anglo – Indian unmarked silver bowl, Madras circa 1900

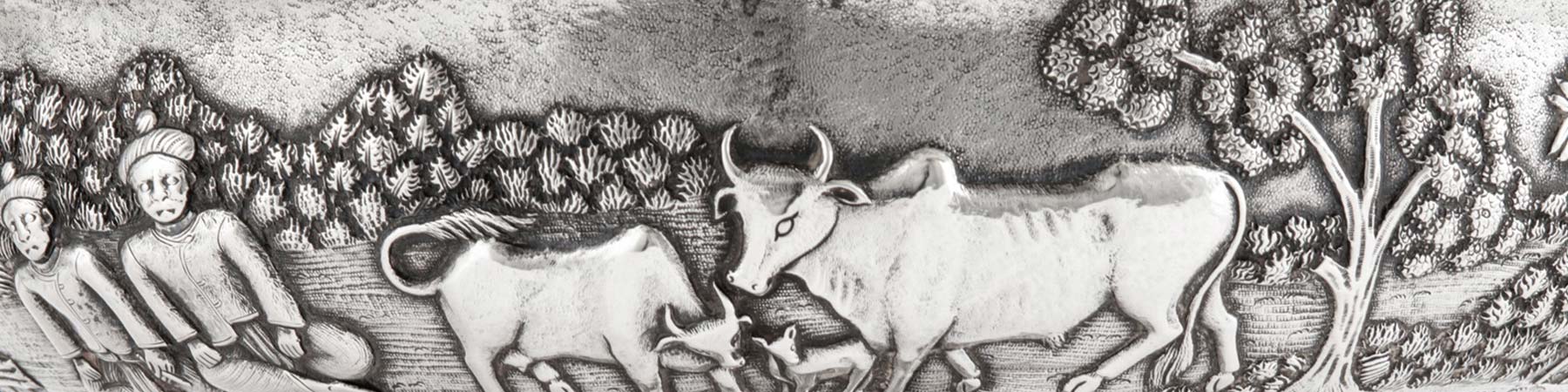

As one of the earliest colonial centres for silversmithing, Calcutta has a long and distinguished tradition. Although initially dominated by European forms, by the late 19th century local artisans introduced new decorative schemes for international exhibitions. These included Village pattern, Bamboo pattern, and River pattern – the latter often incorporating the mythological sea creature Makara.

The suburb of Bhowanipore became a hub for production, with the Dass and Dutt families among the most prominent names.

Lucknow is one of the most prolific centres of Anglo-Indian silver. It is known for its distinctively shaped vessels and broad stylistic range. Lucknow artisans were especially adept at imitating patterns from other Indian regions, and even foreign styles such as Burmese silver. Typical motifs include hunting scenes, twin fish (symbolic of the royal insignia of Awadh), and dense figural decoration.

The city’s silversmiths demonstrated exceptional creativity in combining Chinese, Burmese, Cutch and regional designs into single objects.

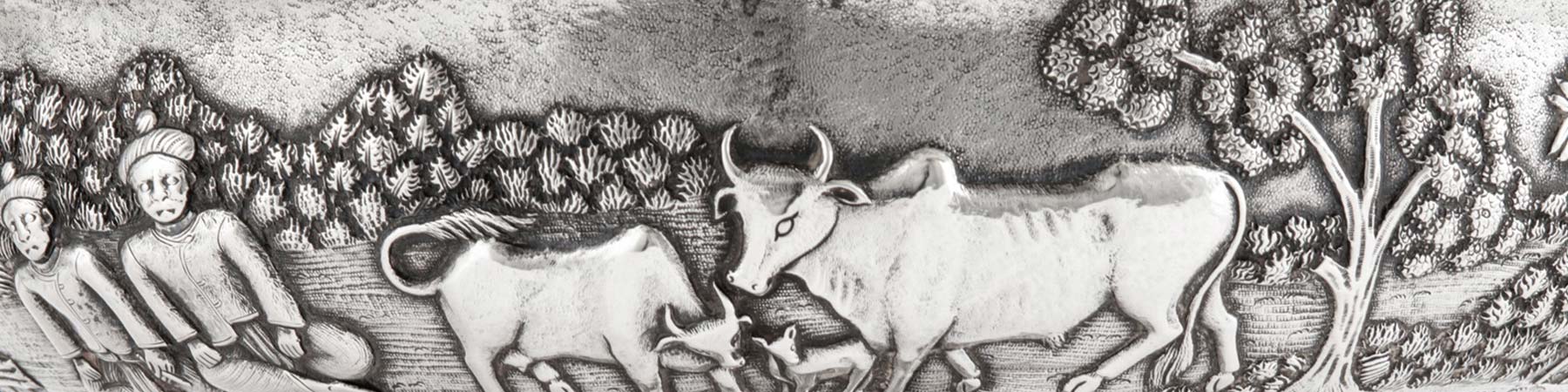

A late 19th / early 20th century Anglo – Indian unmarked silver bowl, Lucknow circa 1900

This form of bowl is typical of the Lucknow region with a convex centre and fold over rim. They are found in a variety of sizes from very small to large and are decorated with usually hunting or Burmese pattern

A late 19th / early 20th century Anglo – Indian unmarked silver bowl, Lucknow circa 1900

Another form of bowl found in the Lucknow area, the intertwined fish feat and the chased fish to the border are distinctive features of Lucknow silver as the twin fish were the chief element of the Royal insignia of Awadh.

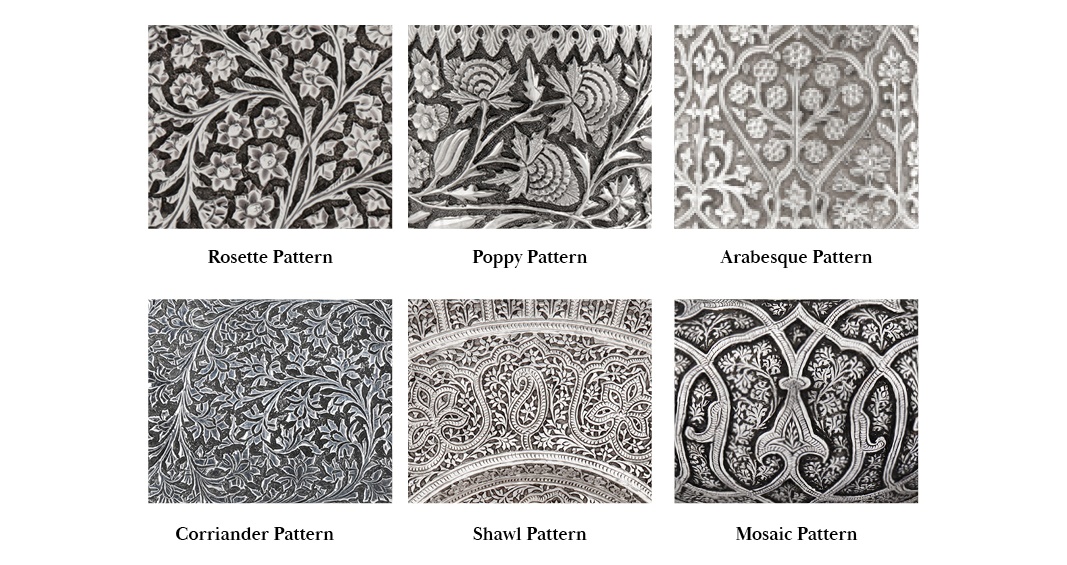

A large late 19th century Anglo – Indian unmarked silver bowl, Lucknow circa 1890

This unusual bowl, maintaining the shaped pierced borders typical of Lucknow has directly copied the figural scenes embossed on Canton made silver exported from China.

This bowl uses the typical Lucknow shape but with Pharaonic type figures which otherwise would have been worked with Burmese style figures. Egypt was under de facto British control from 1882-1956, so this bowl may have been for exhibition in Cairo or sold as part of the general appreciation of Indian made wares with British consumers.

A late 19th / early 20th century Anglo – Indian unmarked silver tea caddy, Lucknow circa 1900

This tea caddy is a distinct Lucknow shape but combines multiple different Lucknow patterns on one object, such as the Chinese inspired chrysanthemum pattern with birds, jungle pattern, bamboo, Cutch type and holy men or yogi.

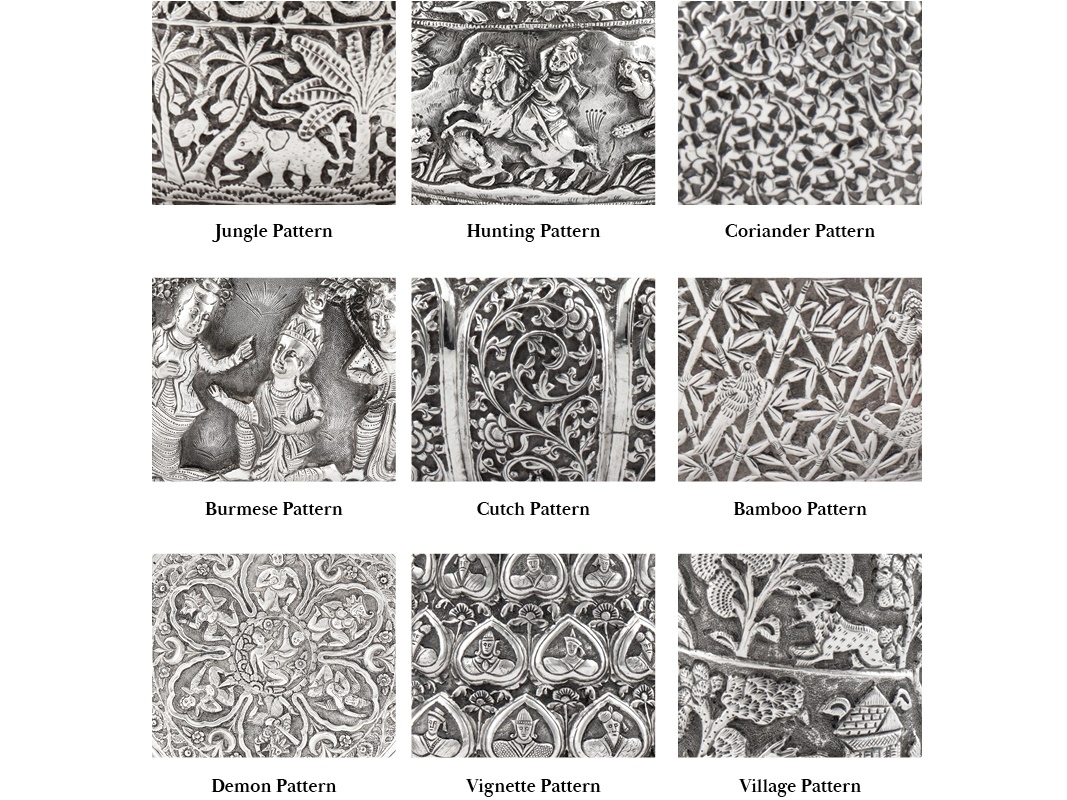

The silverware of Kashmir is closely linked with the region’s renowned textile traditions. Local artisans translated intricate patterns from shawl weaving and architectural elements into metalwork. Common forms include trays, trophy cups, condiments, mugs and the distinctive chinar-leaf dishes. Kashmir silver often features all-over surface decoration, with patterns such as Shawl, Arabesque and Mosaic, sometimes accented with enamel.

A large late 19th century Anglo – Indian unmarked silver mug, Kashmir circa 1880

A rare mid to late 19th century Anglo - Indian silver butter dish on stand, Kashmir circa 1870

A late 19th century Anglo – Indian unmarked silver twin handled cup, Kashmir dated 1887

After the 1899 earthquake in Cutch, many skilled silversmiths relocated to Karachi. The style they brought with them preserved the hallmarks of Cutch craftsmanship, including highly detailed chasing and animal motifs. Quality Karachi silver is usually marked with the maker’s name and ‘KARACHI’, with notable names including Soosania and J. Manikrai.

A rare early 20th century Anglo – Indian silver table casket, Karachi circa 1920 by Soosania

A rare early 20th century Anglo – Indian silver tea caddy, Karachi circa 1920 by J. Manikrai

A rare early 20th century Anglo – Indian silver teapot, Karachi circa 1920, marked LM (untraced)

Examples of the form of maker’ s marks found on Karachi silver

As a major metropolitan centre, Bombay attracted silversmiths from across India. Much of the silver produced here is indistinguishable from Cutch silver due to the movement of artisans. Bombay also developed a Swami style distinct from Madras, typically including elephant-head spouts and handles. Hill village scenes and hunting vignettes were also popular decorative elements.

An early 20th century Anglo – Indian unmarked silver tea service, Bombay circa 1910

An early 20th century Anglo – Indian unmarked silver footed bowl, Bombay circa 1920

Poona silver is closely linked to Cutch traditions but incorporates Burmese influences and unusual decorative features such as demon masks. The work of Heerappa Boochena is especially prized, known for finely embossed figural scenes within architectural arches. The diversity of motifs and hybrid patterns in Poona silver remains a subject ripe for further research.

A large late 19th century Anglo – Indian unmarked silver bowl, Poona circa 1890

Cutch silver remains the most celebrated and collectible of all Anglo-Indian silver. Recognised for its intricate scrollwork, rosettes and animal motifs, it was widely admired in India and internationally. The high purity silver and labour-intensive chasing technique produced works of outstanding craftsmanship. Oomersi Mawji, whose pieces are now held in major museum collections, is considered the finest silversmith of his time.

His legacy, along with that of his sons, helped elevate Cutch silver to a true art form

A late 19th century Anglo – Indian unmarked silver claret jug or ewer, Cutch circa 1870

Whether you are a seasoned collector or exploring the world of Anglo-Indian silver for the first time, understanding the regional differences and stylistic nuances can greatly enhance your appreciation of these remarkable works.

If you are interested in receiving a complimentary Silver & Objects of Vertu valuation, get in touch with Head of Department John Rogers at john.rogers@chiswickauctions.co.uk or submit an Online Valuation today.