16th Apr, 2021 13:00

Islamic & Indian Art

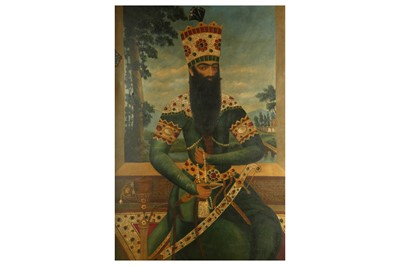

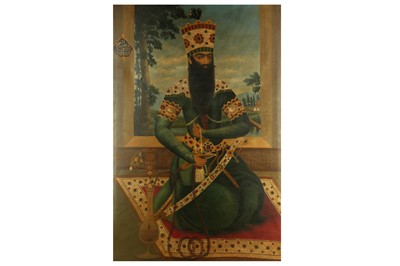

A SEATED PORTRAIT OF FATH 'ALI SHAH QAJAR (R. 1797 - 1834)

Possibly Tehran, late Qajar Iran, ca. 1910 - 1920

A SEATED PORTRAIT OF FATH 'ALI SHAH QAJAR (R. 1797 - 1834)

PROPERTY FROM A PRIVATE UK COLLECTION

Possibly Tehran, late Qajar Iran, ca. 1910 - 1920

Oil on canvas, a seated portrait of the second and most renowned Shah of the Qajar dynasty, Fath 'Ali Shah, depicted kneeling on a red carpet with jewelled borders with pearls, emeralds and spinels, his fully encrusted sword resting on his lap, the Shah wearing a green robe, the bejewelled imperial crown and two heavily encrusted bazubands, one on each forearm, a khanjar dagger tucked into his belt, holding in his left hand a pearl rosary and in the right one the crystal mouthpiece of a qalyan (water pipe), behind him a wide-open window projecting onto a stream flanked by verdant trees, an ochre-coloured building in the background to the right with an arched portico reminiscent of the buildings in the garden of the Negarestan Palace, the Shah's favourite retreat, on the top left a cusped black cartouche outlined in yellow inscribed Al-Sultan Shah Fath 'Ali Qajar, within a black wooden frame, 116cm x 77cm excluding the frame.

Provenance: purchased at the Mathaf Gallery in Belgravia, London, in the early 1990s and in a private UK collection since.

More images of Fath 'Ali Shah Qajar have survived than of any other Persian rulers and their iconography was dictated by very clear and precise indications (L.S. Diba and M. Ekhtiar, Royal Persian Paintings: the Qajar Epoch, 1785-1925, Brooklyn, 1998, p. 180). When portrayed alone, the ruler was most frequently depicted seated on a bejewelled floor spread; when accompanied by his sons and courtiers, he was instead depicted enthroned, standing with his staff of state, or clad in ceremonial armour. Nothing was left to chance: every portrait encapsulated the essence of the Shah's ambition of constructing a long-lasting dynastic image of himself and his progeny. Indeed, as Layla S. Diba explains, Fath 'Ali Shah's reign was characterised by the consolidation of the machinery of power and the formulation of a specific and precise poetic and visual repertoire to celebrate his achievements; link him to his royal predecessors; and proclaim himself as the rightful and most enlightened ruler of the Qajar dynasty (Ibidem, p. 35).

His artistic Bazgasht (return - Renaissance) and the establishment of impactful life-size royal paintings played a critical role in the consolidation of early Qajar power. The emphasis on the formulation of a dynastic image increased drastically with the ruler's accession in 1798, when he started fostering a very precise iconographic and decorative program entailing multi-image cycles and monumental compositions (Ibidem, p. 37). From that moment onward, images of the Shah and his entourage would dress walls, niches, arches and halls of Qajar palaces, enacting a true form of visual propaganda. During the turmoils of the last twenty years of his reign, when life-size paintings ceased to suffice, Fath 'Ali Shah proudly commissioned monumental figural rock reliefs, placing himself side-by-side with the great Achaemenid and Sasanian kings of the Persian past.

The Shah's artistic patronage and relentless focus on the establishment of an iconic pictorial language for royal portraits had a long-lasting impact on the art of 19th-century Iranian painting. Indeed, in the second half of the 19th century, when Qajar society was marked by drastic changes, the Shah's grandson, Nasir al-Din Shah (1831 - 1896) followed his footsteps in attempting to initiate change through extensive patronage of artists and schools of arts, like the Dar al-Funun Academy (Ibidem, p. 239). However, differently from Fath 'Ali Shah, Nasir al-Din fostered an image of monarchy that combined traditional Persian kingship's ideals and conservatism with modernity, deriving from the influence and constant relations with European powers and practices. Life-size paintings were soon overthrown by black and white photographs, lithographs and European easel paintings.

The final years of the Qajar dynasty were marked by political unrest and drastic social changes, leading to the end of the courtly arts' patronage, including painting. Nevertheless, the educated elite continued to portray the evolution and developments unfolding within the Iranian society as faithfully as a camera, at times accentuating the drastic contrasts between local traditions and forced Westernisation with caricatures; other times indulging into an ode to the past, a 'divorce from reality', as Amanat would call it (A. Amanat, "Russian Intrusion into the Guarded Domain" in Journal of the American Oriental Society 113, 1993, p. 36). It is exactly around this time that many life-size paintings and frescoes of the Negarestan Palace started being emulated and copied in the format of portable oils on canvas, pencil sketches or gouaches on paper by skilled painters, such as Samsam Ibn Zulfaqar Musavvir al-Mamalik. These official copies, of which a dozen are known and whose originals are now mostly destroyed, served the scope of preserving the dynastic image of Qajar rulers, glorifying their power even at the sunset of their era (G. Fellinger in L'Empire des Roses: Chefs-d'oeuvre de l'art persan du XIXe siecle, Louvre-Lens, 2018, pp. 294 - 297).

Our painting embodies all the quintessential features of the last Qajar school of royal portraiture. The portrait is imbued with a nostalgic flare and pays tribute to a pictorial tradition that turned upside down the concept of Persian painting; a tradition that departed from the small-scale intimate miniatures of pre-Qajar times, and reached monumental sizes. The ruler's iconography is perfectly in line with the canons established under Fath 'Ali Shah's rule and yet, it was produced approximately 100 years later. Even the Shah's expression seems calmer and more tamed compared to earlier portraits produced at the peak of his reign, which we can see in the Hermitage Museum's collection. The brush stippling technique employed to create a charming relief on the gems and pearls is indebted to the paintings produced at the end of the 18th - early 19th century, and so is the cusped cartouche bearing the Shah's name, as if it was necessary to clarify whose portrait it was. The bucolic and tranquil background resonates with contemporary European paintings, a considerable change from the fast and opulence of the Qajar palaces' interiors, the usual backdrop of earlier creations. And yet, despite these modern influences, the portrait respectfully honours the great tradition established by Fath 'Ali Shah, acting as a true swan song, as one last hurrah for the Qajar dynasty and the traditions rooted in Pre-modern Iran.

Do you have an item similar to the item above? If so please click the link below to submit a free online valuation request through our website.