Harold Cohen : The First Digital Artist

Long before Cohen become a pioneer of computer art, at the age of 38, he was a painter with a well-established career and one of those selected to show at the 33rd Venice Biennale in 1966. Lot 323 in our upcoming Modern & Post-War British Art auction on 22 April 2021 was exhibited here. In 1966, Lilian Somerville and her committee aimed to showcase a new spirit of British art at the biennale by bringing together an exhibition of sculptures by Anthony Caro and paintings by Bernard Cohen, Harold Cohen, Robyn Denny and Richard Smith. The title of the exhibition was Five Young British Artists.

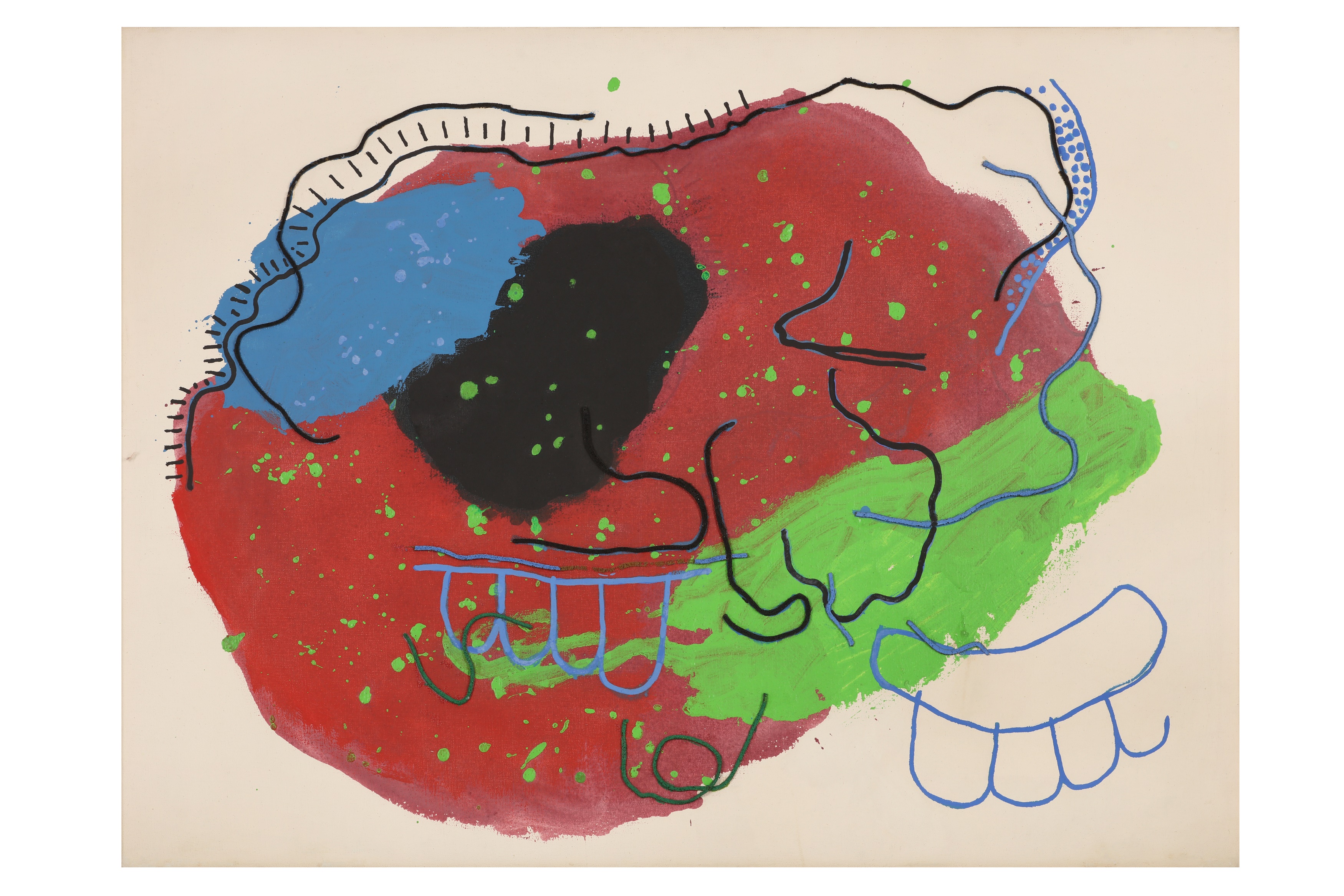

Lot 323. Harold Cohen (1928-2016), Central, 76 x 102 cm (30 x 40 1/4 in). Modern & Post-War British Art, 22 April.

In this context, David Thompson, the author of Venice Biennale: the British five, differentiates Cohen's work:

“In a Harold Cohen painting there will be fragmentary linear movements and various areas of textured or flat colour where the tensions arise from the way they grow together – a dappled background intuitively suggesting the movement of line, line intuitively suggesting enclosed or partly enclosed shapes and colour areas – so that the results are both seemingly casual and organically close-knit: images, references, contradictions and possibilities are implicit at every stage – the inside of a line, for example, defining a shape; the outside of it apparently suggesting a spatial boundary; and the way it abruptly comes to an end leaving both interpretations open.”

AARON Paint System on display at the Computer History Museum in Revolution: The First 2000 Years of Computing.

It was following this success that Cohen began exploring the creation of AARON in 1973, which has been in constant development ever since. Initial versions of AARON created abstract drawings that grew more complex throughout the first decade of its existence. This imagery later became more representational into the 1980s; first rocks, then plants, then people. In the 1990s, this transitioned into figures set within interiors. AARON then returned to more abstract imagery, this time in colour, in the early 2000s. Previously, the drawings were done by the drawing machine or printed on plotters, and Cohen would insert colour by hand. Teaching the program to colour was one of Cohen’s biggest challenges. He said:

“There was no colour monitor when I started. So, there was no way to talk about colours with the machine. Later, the main problem was that my program was smart enough to do the drawings, but I had to come over and colour the drawing afterwards. The program does not have eyes, so it could not have the same visual feedback system that a human being colourist has. Instead of thinking about what it couldn’t do, I started to think about what it could do. And I suddenly realised that the computer can do something that human beings can’t. Once it makes marks in colour, it has an impeccable memory of what was there. The programme started to ‘colour adequately’.”

The first colour image created by AARON at the Computer Museum, Boston, MA, in 1995. Collection of the Computer History Museum 102741168.

In the 1990s, once Cohen had enabled AARON to produce colour and no longer had to colour the images by hand using fabric dye (Procion), he built a series of digital painting machines to output AARON's images in ink and fabric dye. His later work used a large-scale inkjet printer on canvas.

AARON cannot learn new styles or imagery on its own; each new capability must be hand-coded by Cohen. Indeed, Cohen is very careful not to claim that AARON is creative. However, he does ask "If what AARON is making is not art, what is it exactly, and in what ways, other than its origin, does it differ from the 'real thing?' If it is not thinking, what exactly is it doing?" Nevertheless, it could be argued that AARON is simply following procedural instructions and that the real artist behind each piece is AARON's creator, Cohen.

The 1995 version of AARON could colour its own images using a variety of brushes and a robotic arm.

In the last few years of his life, Cohen moved towards a more collaborative role with his creation for the exhibition Collaborations with My Other Self, at the UCSD gallery in 2011. For this exhibition he returned to the paints and brushes. In addition to showing works totally done by his digital other self, AARON, he made the program create patterns on only one plane so that he would paint on top himself. Cohen recalls that he had missed the tactile feeling of painting. He resultantly worked on improving the program’s interface so that it could work on a touchscreen. This enabled him to set up a 50-inch monitor where he would choose colours with his fingertips to finalise the Aaron-generated drawing.

Cohen was an artist who has changed the way we came to understand the interaction between art and technology. This is very relevant during current times when the relationship between art and technology is at the forefront of many minds. Indeed, only three years ago in 2018, Portrait of Edmond Belamy created by Obvious, a Parisian collective, sold for £ 312,600 at Christie’s, nearly 45 times its high estimate. This was the first work of art created by an algorithm to ever be offered at auction. Similarly, just last month Christie’s sold the Beeple NFT Jpeg for £50 million. Since then, Sotheby’s has held the first ever auction purely consisting of NFT works with digital creator Pak, where £12.3 million was realised. This use of artificial intelligence (AI) to produce art and the development of NFTs very likely took influence from Cohen’s developments in creating AARON.

Modern & Post-War British Art, Thursday 22 April at 2pm.