Chinese Painters - A beginners guide for collectors

20/10/2018 Chiswick Curates, Asian Art

With their misty mountains in black inky tones, Chinese paintings are often considered to be the most remote and esoteric area of Chinese art.

And yet, Chinese paintings have received a huge boom in recent years and almost half of all auction revenue within mainland China comes from the sale of Chinese paintings. Indeed, Chiswick Auctions house record was set in 2017 by the sale of a 30 metre long handscroll by Qing artist Xu Naigu which sold for 267,600 GBP [figure 1]. Figure 1.

Figure 1.

But the prices achieved for the top Chinese ink paintings still lags behind those of Western oil paintings and are internationally considered difficult to appreciate by a Western audience. This is despite forming part of a rich and complex 5000 year art historical tradition.

So why are Chinese paintings so difficult? Certainly the aesthetics and styles might be considered very different but Chinese paintings also have a strong link to culturally specific Chinese literature often being paired with calligraphic poetic inscriptions.

Furthermore, dating and attribution issues plague Chinese paintings and the lack of academic consensus is so great that dedicated auction sales of Chinese paintings will never guarantee dating and attributions citing the limits of current scholarship. This places the amateur collector in a strong position as much still rests on taste and judgement.

For those approaching Chinese paintings for the very first time, however, there are a few things to consider that can help frame the way that you look at Chinese paintings: format, subject matter and dating.

FORMAT

Chinese paintings will generally fall into a four categories of display. Whilst paintings are often now framed involving their removal from the original mounting context, the forms of hanging scroll, handscrolls, albums and fan leaves have significant functional advantages.

Hanging scrolls are the most common format for Chinese paintings [see figures 3, 4, 5 and 7]. These scrolls unravel vertically and are typically displayed on a wall. In Classical times they were also unravelled on a pole to be viewed at outdoor gatherings. The hanging scroll has the distinct advantage of being easy to store and switch between works to add variety in an interior display. Other formats such as album leaves and fan leaves will often be found remounted as hanging scrolls.

[gallery size="medium" columns="4" ids="150530,150531,150532,150534"]

Handscrolls are unfolded horizontally section by section, allowing a usually expansive scene to unravel gradually [see figure 1]. They are also suited to the addition of colophons – additions of calligraphic inscriptions by later generations of admirers and collections, often remounted to the left of the original work.

Albums often include one or two dozen small scale paintings bound together in a book format. They might comprise either of a series of works by an individual artist, or a collaboration between a group of associated artists.

Fan leaves are paintings created to be mounted into fans. They are sometimes bound into albums and due to their fragile practical function, they generally date to the 18th Century or later with earlier examples rarely surviving [see figure 2 for a painting still mounted as a fan].

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

DATING

Indeed the dating of Chinese paintings is another important issue to consider for those interested in collecting Chinese paintings. Chinese artists traditionally learnt their craft by faithfully copying works of the masters and copies, fakes and works created in tribute to earlier masters certainly proliferate in the market place. However, most basically Chinese ink paintings can be separated into the Classical, Early Modern, 20th Century works and contemporary works.

Classical works of the 12th and 13th Century are almost all confined to the great museum collections and the works most widely available on the market date to the 18th and 19th Century in the Qing Dynasty. Their creators exemplified the literati class of gentlemen scholars. However, even Emperors made themselves accomplished at painting and calligraphy. Chiswick Auctions will offer a work of calligraphy by the great Qianlong Emperor of the 18th Century in Fine Chinese Paintings on 12 November 2018 [figure 3].

The Classical tradition began to erode in the early Modern period with the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1912. Some artists, a product of the Dynastic era, continued to paint, among those were people like Pu Ru (1896 – 1963), cousin of the last Emperor of China [figure 4].

However, it is modernist painters of the 20th Century who are among some of the most highly regarded artists by the market today. People like Qi Baishi (1864 – 1957), Zhang Daqian (1899 – 1983) and Huang Binhong (1854 – 1955) [figure 5] took the traditional medium of ink and colour on paper and took on Western and modernising influences.

Most radical, however are perhaps those works by contemporary artists which address movements such as abstract expressionism and depart greatly from the traditional medium [figure 6]. Figure 6.

Figure 6.

SUBJECT MATTER

However, abstraction has always a part of Chinese landscape paintings – a predominant subject matter within Chinese paintings [see figure 1, 5 and 6].

Aside from this calligraphy is another important subject matter. Chinese script, partially pictographic is elevated into an art form and calligraphy can either be added to a painting, or written as a complete artwork in its own right [figure 7].

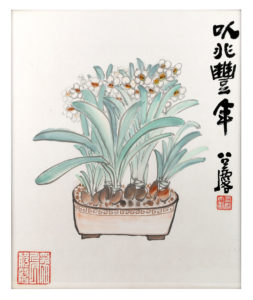

Other popular genres of painting include bird and flower painting [figure 8] and figurative paintings [see figure 4]. Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Chinese paintings is a rewarding area of collecting and represent the cutting edge of Chinese art. They can be appreciated on many levels and at many price points and there are plenty of treasures out there still waiting to be discovered.

Lazarus Halstead is head of Asian Art at Chiswick Auctions. He is one of the leading specialist in Chinese Paintings in the country and studied Chinese Paintings at Oxford University and Peking University. He can be contacted for complementary valuations on lazarus@chiswickauctions.co.uk, or 07906 210 067.

Last year he set up dedicated Fine Chinese Paintings sales at Chiswick Auctions – the only dedicated sales of Chinese Paintings in London.

FINE CHINESE PAINTINGS will be held on 12 November 2018 at Chiswick Auctions, 1 Colville Road, London, W3 8BL.